For almost fifteen years, the Canadian Army has been without an organic air defence capability.

The last such system able to engage targets in the air was the Air Defense Anti-Tank System. As the name implied, this dual-use system was designed to engage both ground and air targets out to 10 km.

ADATS was retired in 2012 amid a series of budget cuts brought on by the then-Harper government, while its replacement, the Multi-Mission Effects Vehicle — which aimed to refine the ADATS concept onto a LAV hull — was cancelled all the way back in 2006.

Of course, almost everyone would agree that ADATS, by that point, was already on the way out. An orphaned fleet, over twenty years old, seldom used, expensive to maintain, and with little value to a government locked into a COIN mindset. It was bound to happen, even with an upgrade program just four years prior.

Before that, the Canadian Army had retired its last man-portable system, the Javelin, all the way back in 2005 — an era when many such capabilities were divested, such as the M109 Self-Propelled Howitzers.

The 2012 cuts had a lasting and profound impact on CAF, one we are still reeling from today. After so long, we finally have an organic capability back in the RBS70NG, which was acquired in 2023 as part of a series of Urgent Operational Requirements to bolster the Multinational Brigade in Latvia (MNB-L).

The systems are finally here, though, and mark a long-fought, monumental achievement for the Canadian Army. This, though, is not the only Ground-Based Air Defence project in the works.

As of now, the Army has three additional projects in the works to supplement the RBS70NG. This includes one additional UOR for Latvia, as well as two identical projects for the wider Army.

These four projects — both UORs and the wider initiatives — mirror each other in terms of demands, though not quite capability. Let’s go through these four projects together.

The Projects

These four projects can be lumped together as part of the Canadian Army's Ground-Based Air Defence Initiative. They are:

The AD-UOR (RBS70NG)

“Uplift” SHORAD-UOR

Enduring Phase II

Enduring Phase III

That might sound a bit confusing, but bear with me. Since we already have the outcome for the AD-UOR, I think we're fine to put it on the back burner for this discussion — at least for now.

Uplift is the cheerful name given to the next UOR related to air defence. Uplift aims to acquire a single battery’s worth of short-range air defence systems to equip MNB-L and complement the RBS70NG.

Uplift is actually the original GBAD project that has been in the works since 2017, before it was split into three phases and moved into the urgent category. This change was a necessity — at least to me — to address the issues the original project had.

And oh boy... Uplift isn’t without its issues.

The Controversy of Uplift

Let’s start by going through the timescale of the GBAD project. The original project aimed to acquire both a VSHORAD and SHORAD system for the Canadian Army. This project was first part of Strong, Secure, Engaged back in 2017.

The requirements for the system were fairly open-ended in terms of what kinds of systems were allowed. Companies were asked to provide solutions to both requirements, with a SHORAD system able to engage targets past 5 km, and a VSHORAD system able to target out to at least 5 km.

These systems could include guns, missiles, or even directed energy weapons. It would also include sensors, fire control software, and an integrated, networked C4ISR system. They would also include simulation and training services.

By the time the ITQ was cancelled in October, four companies had qualified. These four will be competing in Uplift, along with a yet-to-be-named fifth:

Saab Canada with the RBS70-based MSHORAD

MBDA Missile Systems with CAMM

Raytheon Canada with Skyhunter

Lockheed Martin and Diehl Defence with the IRIS-T SLS

All very capable systems in their own regard, and the lineup you would expect for a project like this. If this were a standard SHORAD competition, I don’t think many would complain.

All fairly simple and standard, right? Well, by the time Uplift awards next year, the project will be just under a decade old. This is a major factor behind a lot of the frustration. It’s been on the docket for a long time and, as things do, priorities and demands have changed.

At that time, the project’s main focus was centered on the threats and lessons taken from Afghanistan. That meant that a major requirement of the system was the ability to perform Counter-Rocket, Artillery, and Mortar (C-RAM) duties.

In fact, the primary responsibility for this system was to counter things like C-RAM, missiles, Class I/II drones, and subsonic cruise missiles. These were the primary threats identified throughout the project, and they remain the primary threats as Uplift keeps the same requirements.

These threats — while valid — are not the threats many will now say are priority. Fixed-wing aircraft, supersonic cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles are now identified by most as the primary areas of concern, especially when discussing the future conflicts we face.

By the time the project had started releasing its qualified bidders list, the world was grappling with a much different environment. The Russian invasion of Ukraine drastically shifted priorities from the COIN-centered operations of most of the 2000s back into the haunting reality that we might have to deal with a near-peer threat — and far sooner than we expected.

Throughout CANSEC, I took the time to talk to whatever manufacturers I could about GBAD and their expectations. This was especially important for me, as it is one of the Army's four priority projects. And while there was hope that Enduring would be different, the requirements for Uplift were seen as a negative step.

For manufacturers, these requirements presented a frustration. They believe the Army is thinking in the past — with requirements that are no longer relevant, or that they are unable to provide. This is especially true of the C-RAM requirements.

It is a holdover of a different era — one where the demands are seen as too much for many of them to meet with their available systems. A C-RAM system is very specialized, one that requires the ability to engage dozens of targets of various sizes within a very small timeframe.

For many of these systems, the number of launchers required to perform this is either rather large or seen as ineffective. Many of them are not optimized to this task — even if they could hypothetically do it.

This I can understand, especially given that these demands remain unchanged. The only system here that really fits this need is the Raytheon Skyhunter system, an Americanized version of the Israeli Iron Dome.

If you remember my discussion from last year, I raised the point that, as it stands, Skyhunter had a very clear avenue for winning. It is the one system that fulfills these demands — and while we might have divested from the effectors side of Ground-Based Air Defence, we still have had the ability to detect and track threats.

For what matters here, that system would be the AN/MPQ-504, more commonly called the Medium Range Radar. This is the designation we use for the ELM-2084 — the same radar used by the Israelis for the Iron Dome.

So you have a system that actively meets these very specific requirements, whose parent system’s radar is already in service with us. It truly feels like everything is coming together for Skyhunter here — and going off these factors, I expect it to come out on top.

For most manufacturers, this represents a disappointment. There was some hope that the breakup would see a shift in priority. I raise a different point — that if things work out, perhaps we might end up better off than merely opening the competition to SHORAD.

That opinion might be controversial, but assuming Skyhunter comes out on top, I can see the value of a C-RAM type system — a cheap, more expendable system that can be used not just against munitions, but also drones and missiles — that fits between the lighter VSHORAD and a traditional SHORAD/MRAD system like CAMM.

Air defence, especially in today’s era, is a complicated system of balancing effectiveness and capability versus cost and performance. You will have to make sacrifices somewhere and will have to accept that you need a true, layered system to be effective.

But we will get to that later. Let’s quickly go into the next phase.

Enduring

We don’t know exactly what Enduring Phase II or III will look like. Both projects are still in the analysis phase, and while we have some info, we don’t have many concrete requirements to go off of.

We can use what we have, though, and assume a bit to get a fairly decent look at what the end result might be. We know that Enduring Phase II will be a SHORAD system, and likely feature most of the same competitors as before. It will also be for a singular battery. We know that there will be greater emphasis put on things such as fixed-wing aircraft.

Enduring Phase II will very likely be a different system than Uplift. It isn’t guaranteed, but depending on how the project trends, this will be likely. For all intents and purposes, as we know now, Enduring Phase II will be a more traditional SHORAD system like CAMM or NASAMS.

For Enduring Phase III, things are a bit more open-ended. We know it will likely be a vehicle-mounted VSHORAD solution, though what exactly that looks like remains to be seen.

It could be something like Saab MSHORAD — integrating the RBS70NG and Giraffe radars onto a future LUV chassis — or it could be more along the lines of Skyranger 30 or the Sgt. Stout LAV seen at CANSEC.

As of right now, both projects remain in the analysis phase, with both aiming to award contracts before 2030. That is a fairly tight timeline for all of this, though not impossible to reach if given the priority that many want to give it.

Sadly, there isn’t a lot that can be said about them at this time. We should be learning more about them soon — especially once more concrete plans for restructuring are set, and we get a better idea of what the future looks like.

But Noah, What About Golden Dome? Where Does It Fall Here?

While I would love to talk about IAMD and Golden Dome, this falls out of the Army scope. That category falls on the RCAF to handle, so we will not be discussing that here. We are focused solely on the existing Army projects. That is an entirely separate discussion.

So We Have All These Projects — How Do We Make This Work?

This is another common question that I’ve received — not just from people around here, but also from some in industry. We have four separate projects, each mirroring the other in capability, at least on paper.

This is before we get into the logistical and financial implications of managing potentially four different systems — especially only a battery of each. This is also before we talk about putting all this on 4GS as well.

As I spoke before, you need layers. You need to be able to have effective, comprehensive coverage against a variety of threats, while making sure it is economically valuable and not overly burdened either in systems or tasks.

That again means sacrifices need to be made — and speaking around, the sacrifices are clear. We would rather deal with those issues and procure four separate systems than sacrifice capability.

We see these issues in Ukraine. The Canadian Army needs to be able to handle a plethora of different threats — from small drones to things like Lancets, cruise missiles, fixed and rotary aircraft, and even ballistic missiles.

It was only last week that we saw the largest air attack of the war to date. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), well over a thousand drones and missiles were launched into Ukraine over a three-day period. In that period, Russia launched over 300 Shahed drones, 21 Iskander SRBMs, and just over 60 air-launched cruise missiles.

According to Ukrainian estimates, Russia likely has around 500 ballistic missiles in its stockpile — and that number is growing. Shahed launches are now breaking a thousand in a week — not a hundred, not five hundred — but a thousand.

The brigade in Latvia, in any conflict, will be at the forefront of such mass-scale attacks, and we need to be prepared — even with limited numbers — to be able to effectively counter that. That requires a diverse, layered air-defence network with assets optimized to handle different threats.

A system like CAMM or NASAMS will do fine for a lot of those higher-end systems, like fixed-wing aircraft, cruise missiles, and even limited ballistic missile defence. Yet a single battery will be overwhelmed — even two — if it is forced to expend itself drone-hunting, or even targeting things like subsonic cruise missiles and glide bombs, another very prevalent and highly destructive tool in Russia’s arsenal.

A system like Skyhunter, though, is far more optimized to deal with those lower-end threats that exist beyond the likes of RBS70NG and Skyranger — but also might be better off not wasting a system like CAMM on.

Think subsonic cruise missiles, glide bombs, or Class IV and above drones. Skyhunter also does provide a C-RAM capability as well — something that, again, while not on anyone's priority, is still a valuable layer to have.

Skyhunter also brings additional depth compared to other SHORAD systems. While something like CAMM-ER can carry eight missiles per launcher, a single Skyhunter can carry twenty Tamir interceptors. When you have such a limited number of launchers — a battery each — having missile depth becomes incredibly important.

Beyond the SHORAD, we will still have the RBS70NG, a very capable and scalable VSHORAD system. Instead of looking for a similar system, Enduring Phase III should work on developing a vehicle-based VSHORAD system, while we allow RBS70NG to take up the man-portable air defence role.

That includes potentially integrating the RBS70NG into whatever comes out of Enduring Phase III, or investigating acquiring the Giraffe-1X radar system to provide light forces with their own vehicle-based VSHORAD system built around the RBS-70NG.

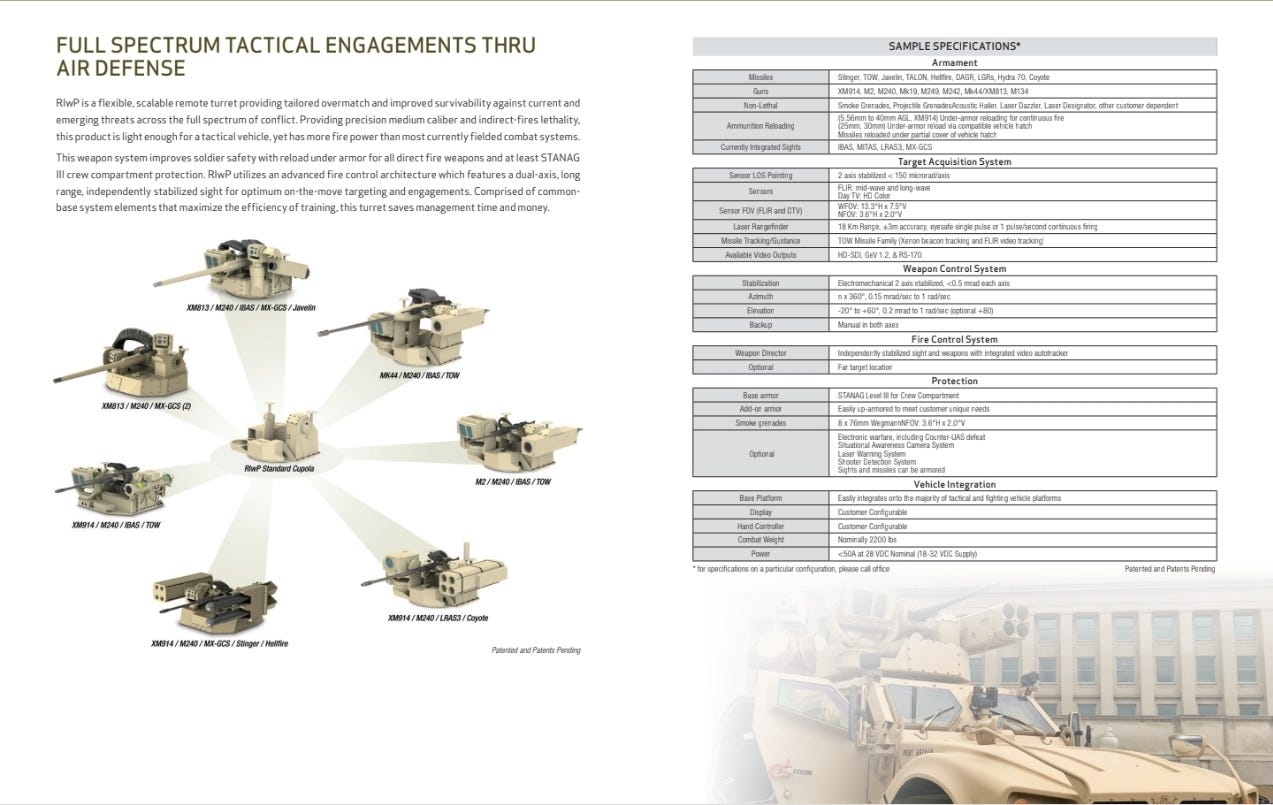

Speaking of Enduring Phase III — while I won’t pretend to know the proper solution — I will say I am a fan of the Moog RiWP turret, as shown at CANSEC this year. Moog has slowly become a common fixture among our allies, both for its cheaper cost and its ability to rapidly shift roles through its modular turret system.

The U.S. Army has already adapted the system as the SGT. Stout. There is already a working concept for us to base around that still gives flexibility to “Canadize” it to our discretion. The RiWP can also easily be adapted to a number of different platforms beyond the LAV family — such as the future LUV.

Common VSHORAD system? With flexibility to be used in other roles? I like that concept a lot. And while I like Skyranger, I would also want to look at where we can acquire additional capabilities beyond that base GBAD requirement (it’s also a bit more future-proof, IMO).

If we can stick to this concept — to accept what we have and use Enduring to expand upon those capabilities — then we could have a fairly well-layered, albeit limited, air defence capability.

It will be more expensive, yes. It will take a lot more effort to make work. That is the sacrifice we take, though, to ensure that we have the capabilities we need to survive against a peer adversary whose aerial capabilities are not only a substantial threat — but growing.

There comes a time when we have to accept that we need to go beyond what we have historically been willing to do — that we are able to do it. The modern world requires us to look to new, sometimes more radical concepts. Concepts that even four years ago, we would see as beyond our reach.

Compared to others, two batteries is little. To us, it is a revival — a return to a force we haven’t seen in decades. And setting ourselves not just for this new capability, but to set ourselves for the future, is what I see as the importance of projects like GBAD.

These are not acquisitions. They are initiatives, whose consequences will be far and great. They will build a foundation for a new Army. We broke this up once. We’ve let this sit. We’ve let it grow outdated. We can’t afford to mess this up again.

You've been busy this week!

Personally, having watched the War in Ukraine very closely, regarding air defence/Anti-drone capabilities, my biggest thought has been “Flak is Back baby!” At the end of the day, aside from lasers (and perhaps EW, but fiber optic lines are hurting that) there’s no more cost-effective way to counter a swarm of drones than with a storm of air bursting fragmented steel. The German Gepards in Ukraine are doing WORK. We’d have to be absolutely CRAZY not to procure at least one platform of M-SHORAD equipped with a cannon (eg. Skyranger).

I think we’ll also have to see a doctrinal change that will see multiple M-SHORAD platforms ride into battle right (like a hundred meters) behind an armoured assault, because it’ll be the only way to ensure that we have enough concentration of air defences to protect the actual assault vehicles. That and i expect assault vehicles will see a redesign over the coming years to make drones less effective.